How Iranians ended up working for the Japanese Yakuza

The Iran-Iraq war and its consequences led Iranians to seek employment opportunities in Japan. However, a deteriorating economy and no means to return home pushed them into a life of crime.

You can find vivid Iranian communities in almost any major city in the Western Hemisphere, yet I had never considered that they must have made it to Japan as well. On a flight from Chicago to Vienna, an Iranian-American, Reza, opened my eyes to the fact that there is, surprisingly, an Iranian community in Japan. Even after Reza had a glass of whiskey–or perhaps more than one– he only briefly talked about his ten year and not entirely legal stay as a migrant worker in Tokyo, which left me with an empty idea of an Iranians life in Japan.

Under Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the governments of Japan and Iran signed a visa-exempt tourism agreement in 1974, which for some reason, lasted well into the Iranian revolution. When the Iran-Iraq war left the Iranian economy in shambles, unskilled laborers migrated to Japan, a country which was just in the middle of an economic boom. The Japanese authorities turned a blind eye to the predominantly illegal labor (as a tourist visa does not permit work) due to the increased demand for workers in construction projects and the unwillingness of the domestic population to take on these jobs. The bubble grows, and in the early ‘90s, the bubble bursts – and suddenly a bunch of Iranians find themselves out of work, in a country which doesn’t really want them. Japan lifted the visa-exempt agreement (and the Iranian government, in its known calm stoic manner, reacted by lifting it as well). With expired visas and without work permits, many Iranians turned to petty crime, or continued to be exploited, and blackmailed, by businesses seeking cheap labor.

As the Iranians that turned to crime didn’t have any connections, or infrastructure in place, they were quickly hired by Japanese organized crime. The “Chinpira”, the lowest ranks of the Yakuza, used Iranians to do their bidding. However, the Iranians were never full-fledged members of the Yakuza, as the group is highly “patriotic”, and would never fully initiate a foreigner. In their own words:

“That's why in our industry (Yakuza), we say "Irapaki" to refer to dirty foreigners. [ed: “Irapaki” referring to Iranians and Pakistanis]”[1]

The low-level Iranian criminals would sell counterfeit telephone cards, which could be used to make international calls at a fraction of the price, or, who would have thought, they would also engage in drug trafficking.

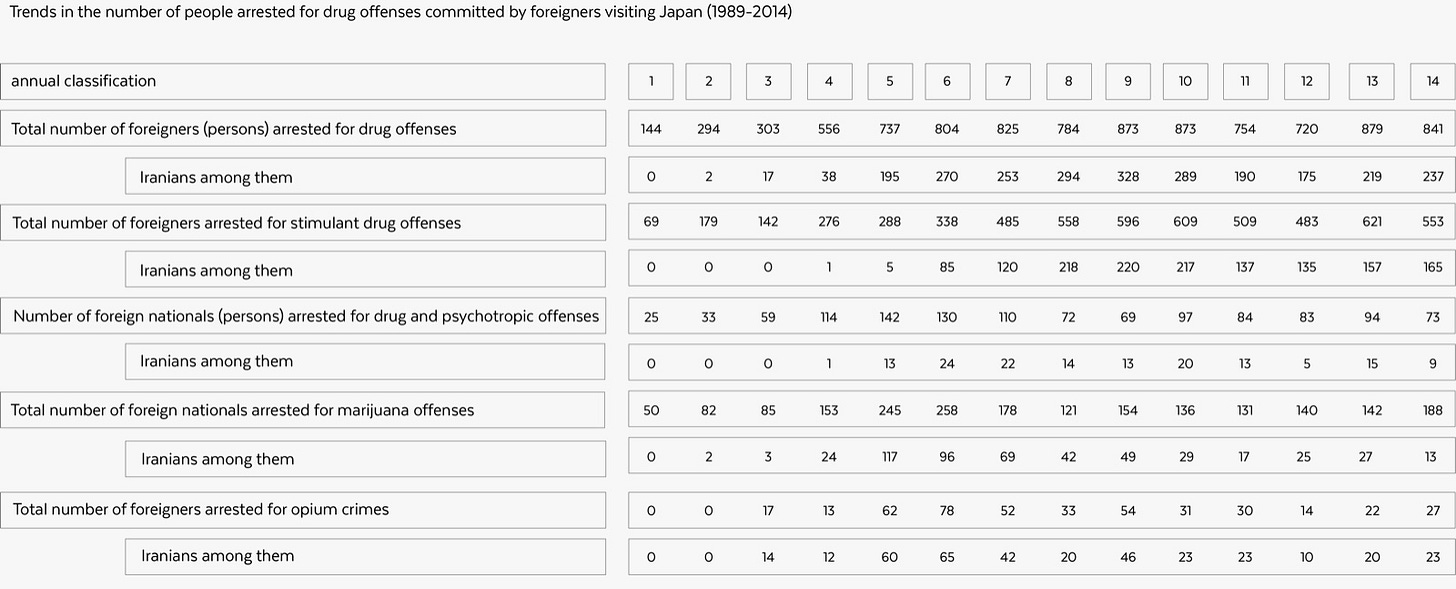

Over time, the Iranian community in Japan, or at least the remnants of the illegal workforce that came chasing the quick money and found themselves stranded in a country that harbors resentment towards them, became organized. They are primarily located in the Tokyo metropolitan area, with some reaching out to the Kansai region. Their influence, or at least their willingness to act, has also increased. This was proven by a murder case that described the perpetrators, as well as the victim, as members of a gang primarily composed of Iranians[2]. Because of the Iranian drug dealers' blatant advertising in public space, they are also involved in turf wars, one of them on the infamous Shibuya crossing[3]. Crime statistics from the National Japanese Police indicate that arrests of Iranian criminals have gone down over the last years, although they still hover in the hundreds.

Except for the occasional case file, not much is reported on their more recent activity, which leaves me wondering as to the current situation of the “Iranian crime syndicate” in Japan. They are simply referred to as passers-by, in statistics or as anecdotes of the problem with illegal immigrants in Japan.

“だから、俺らの業界(ヤクザ)では、ヨゴレ外人を指して「イラパキ」と言う” from “A former organized crime group member frankly reveals the dangerous reality of underground dealings with foreign countries" by Noboru Hirosue.

I wonder how Reza is getting on…

Solid Content